Tom Walters outside the green shed at Matakana Oysters

Oysters for the People, Shit in the River

4th August, 2025

The awa is poisoned, the oysters can’t be harvested, and the system meant to protect both has failed. In Mahurangi, one farmer stands between survival and collapse. North & South’s Sarah Daniell investigates the regulatory failures, climate impacts and rising toll on the community and small business owners like Tom Walters.

In a green shed just past the turn off to the Matakana, I’m handed a cup of oyster soup. I take a slurp in the same way you might neck a whole oyster. It’s an elegant, high-toned revelation in a recycled cup.

The recipe is Tom Walters’, but not the oysters. They came from Peiwhairangi (Bay of Islands). Walters was given the oysters in exchange for oyster wood, a specific material used for building oyster farms. Old-school commerce: I’ll give you this if you give me that. If it sounds romantic it’s anything but. It’s an exchange born of necessity. He would’ve paid for the oysters but he can’t.

Weekenders, tourists and commuters driving north to Te Tai Tokerau, or south to Tāmaki Makaurau, take the detour off the main drag to buy a dozen in the half shell for $25, or shucked in pottles. They are, like the sign above the green shed says, “Oysters for the People”. Walters wants to keep the doors open, so he sources the shellfish from elsewhere. To close would mean giving up. So he’s hanging in there. Just.

Matakana Oysters is legendary because of the product – sweet, plump Mahurangi oysters – but also for the charismatic character at the helm for 20 years. Walters is weeding a flower bed outside the shed when I arrive, because there’s not much else he can do – he’s on week 16 of a shutdown by norovirus caused by sewage and storm water overflow into Mahurangi awa and the harbour.

Norovirus is highly infectious, so it spreads easily. Symptoms can include fever and severe stomach upsets and is a common cause of gastroenteritis outbreaks, says a report in the NZ Medical Journal. “The illness presents with rapid onset of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Vomiting occurs in greater than 50 percent of cases, the median incubation period is 24 to 48 hours and there is an average duration of 12 to 60 hours.”

It was the oyster farmers who alerted those authorities to the presence of norovirus. Those charged with managing the infrastructure and waterways were oblivious, and so too the public, were it not for farmers being on the case.

***

WALTERS wears gumboots and an abundant beard. Inside the shed is a small shop, beyond that, a work bench for shucking and processing plus an impressive wall of vinyl. Walters can’t pick a favourite among the hundreds, but it’s an eclectic mix from 80s new romantic to reggae and Fleetwood Mac. Today there’s no music playing. Inside, the sense of emptiness is palpable. No work to do. No banter. No after mahi beers.

Outside the wolves are baying. There are bills to pay. Walters can’t harvest. There’s no other way of saying this – if you polish a turd it’s still a turd: but there’s shit in the river and it’s spilling into the harbour and flowing down the streets of Warkworth.

Just for a moment, though, standing outside in the sun with Walters, as he leans against a bright yellow ute, that glorious cup of soup tastes like optimism.

Optimism is about all Walters has right now. The shed was built to withstand the storms, however they came. If this were a fable, it’s got the Brothers Grimm written all over it. Outside forces – namely Auckland Council and Watercare – are testing the resilience and the very survival of small farmers and business owners like Walters, and most importantly the environment, which is over-burdened by development, despite prevailing climate wisdom.

“They don’t give a shit about the environment,” says Walters.

The shop inside the Green Shed.

A cup of heaven at Matakana Oysters.

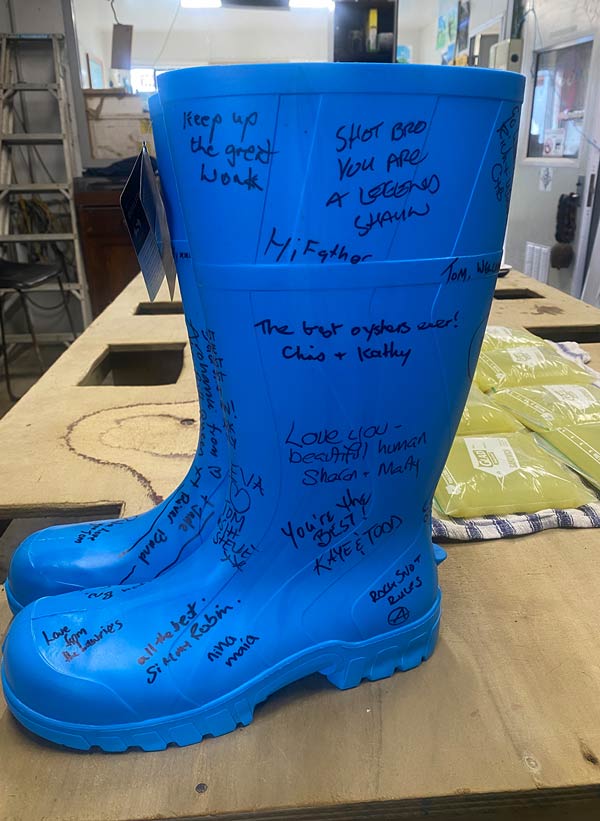

Messages of support from the community on blue gumboots.

Businesses like Walters’ help form the identity of small towns like Matakana and Warkworth. They’re in for the long game. But when the foundations on which you build a future are undermined by infrastructure neglect and mismanagement beyond your control, they’re pushing the proverbial up a hill with a pointed stick.

The cost of the shutdown to his turnover is mounting. Walters calculates it to be around $200,000 this year and $300,000 in the last five years, not to mention unpaid rent penalties, IRD penalties and interest. He reckons it’s actually probably more but it’s hard to quantify.

“Yesterday I was swept up in a deep sadness as I watched and smelled the sewage run into the awa, destroying the environment. It’s just not okay.”

Walters operates using an old-school, low-environmental impact method and philosophy and he’s pragmatic – he has to factor in closures because of the very nature of the business. He has to be vigilant because their reputation depends on it.

“We’ve had crises in the past. We’ve had massive crises in the past; growing oysters is one of those things that there’s a lot of risks associated with open ocean and water, obviously.

“Even after Cyclone Gabrielle, anniversary floods, the algal blooms we’ve had, crisis after crisis after crisis, nothing compares to this one, which was created solely by Auckland Council, and sadly they wouldn’t care.”

Despite pleading with Watercare and Auckland Council to install a temporary fix, to mitigate against inevitable overflows, he says he and others in the industry were ignored.

Five years ago, the town was at carrying capacity for its sewage.

Auckland Council wouldn’t reveal the total number of consents that have been approved since 2020 or the total revenue. The query is now subject to an OIA request.

Auckland Council is self-regulating, and has refused to admit accountability or offer financial compensation to businesses. Watercare won’t apologise or offer compensation to businesses, but it has offered $55,000 to farmers for psychotherapy through ‘Fish Mate’, a support organisation for ‘our seafood whanau’.

When asked whether he saw the irony of Watercare providing money for counselling for farmers that they wouldn’t have needed had Watercare and Council managed the collapse of infrastructure properly five years ago, Watercare CEO, Jamie Sinclair, said:

“Look, I don’t agree that there’s been no action. I think we’ve been engaging with that community for the last six years and we will have invested by the end of this project $450 million in the Warkworth community. And we’ve significantly re-remodeled the entire wastewater network to address these issues. Now the scale of the plant and the pump station and the adjoining infrastructure will create a long-term benefit for the growth in that area of Auckland, but also to manage the environmental overflows.

“Absolutely I’d acknowledge the stress on the oyster farmers and other businesses as we’ve gone through these works. I met with them in person in May and we’ve engaged with them very closely over those years, particularly sharing information on when things have happened and tried to maintain a very open line of communication. We looked for ways that we could provide some form of support for the oyster farmers. We felt like being supportive for them at this time was appropriate and something we could do.”

On Watercare’s website there is an invitation to “learn about our organisation and how we supply Auckland’s people with safe drinking water and reliable wastewater services … together we can ensure local communities have safe and reliable water and wastewater services that meet the needs of current and future generations.”

The road to hell is paved with corporate mission statements.

Warkworth shops and businesses

The greatest issue is, of course, climate change. The frequency and intensity of flooding and extreme weather events has intensified in the area in the past five years.

But in the past three years, says Walters, it’s really started ramping up.

“Each year we’ve had more closures due to sewage spills or overflows from the river affecting the areas where we grow our oysters.”

This year, though, the harbour’s been closed since the middle of April, and since then he, like other farmers, have been unable to harvest a single oyster.

The overflows, he says, have increased 10-fold each previous year. And this year, it got way worse.

“What happens with these sewage overflows is that when we do norovirus testing in our oysters and our water, the Ministry of Primary Industries, which governs our shores through their strict criteria of oyster farming, will close us for 28 days. That’s a blanket 28-day closure.

“Since April, when we’ve almost been able to test again, we’ve had more rain, huge amounts of spills, and we just get closed again for 28 days. That was about 300,000 litres. Once again, that’s closed us for 28 days, so it’s an ongoing thing,” says Walters.

***

WALKING along Elizabeth Street, the main drag in Puhinui (Warkworth) there’s a collection of shops, bakeries and cafes. It’s a quiet, almost quaint town, 50-minute drive from Auckland. Quaint, like the ancient clay pipes that haven’t been for purpose for decades considering the growth and development in the area.

The Mahurangi River, also known as Awa Waihē, begins as two branches that converge and flow through the town of Puhinui, before dispersing into an estuary and then Mahurangi Harbour. The harbour then opens into the Hauraki Gulf. There are concerns the spills will impact areas like Ōrewa and beyond.

Warkworth – a river runs through it but right now you wouldn’t want to go near it or in it.

Three days before North & South took a town tour, there’d been another sewage spill, timed just as weekend holiday makers and tourists – the life-blood of the local economy – would head to their baches, to vineyards and markets where local food producers sell their wares. To paddle board on the awa, or throw a line out and maybe catch something. To walk the dog.

At the top of Elizabeth St, where the overflow pipe is, is the Bin Inn – a wholefoods market, a curtain maker, a Thai massage salon, and a designer fashion store.

Those approached were reluctant to comment on the record. But one said that outside her shop, raw sewage sprang up like a geyser from a manhole onto the streets. Passersby, oblivious, walked right through it with their dogs and into shops. She rang Watercare on Friday, the day of the deluge, and it wasn’t till the following Tuesday that Watercare workers appeared and fixed the problem. Four days later.

When asked about the delay in fixing a potentially serious public health hazard, Watercare’s CEO responded saying there were no records of the complaint and blamed the manhole breach on “vandals”.

“Unfortunately these bolts have been removed by a member of the public on a number of occasions recently. This vandalism has led to overflows on the footpath and street during wet weather.”

Walters dismisses that claim saying the manhole bolts would need a heavy duty drill to undo, and considering the cameras everywhere “there’s no way any member of the public would do it”.

“We have been accused in an unofficial way before, however I was there once and Downer themselves had taken the bolts off to release the pressure from flooding the shops’ basements. It all ends up in the river regardless.”

Auckland’s Mayor Wayne Brown enjoys the natural beauty the area is renowned for. He spent a day on the awa in his boat last summer, before getting snagged and, according to a local, managing to free himself using a branch. Gallant stuff. Despite the brilliant sunny days lately, awa adventures are off limits for Brown, or anyone else.

North & South asked Brown why, if Auckland Council, was aware of the impact of development on a woefully shambolic infrastructure, did it continue to approve consents and accept fees for residential and other developments, particularly in a time of increased flooding on impermeable land. And why did it take farmers like Walters to alert Council and Watercare of the presence of the norovirus?

“I have sympathy with the challenges faced by the Mahurangi oyster farmers,” said Brown, “and appreciate the farmers bringing this to our attention.”

He added that Auckland Council and Watercare agreed just last year to restrict new connections (aside from those previously consented) in the Warkworth area to manage capacity constraints until the growth servicing pipeline is commissioned in late 2027.

“While I’ve received advice Watercare is not in breach of its consent, this issue can’t be ignored, and we’re asking the [Auckland Council] Chief Executive to report back on options to address this situation [like the installation of a larger wastewater pipe along key sites on Elizabeth St] while it focuses on a long-term solution,” said Brown.

The dam, however, has burst. The damage is done with farmers and businesses like Walters dealing with the fallout.

The fine print on a public hazard sign by the awa.

Sodden and polluted – the awa spills on to the park and pavements near Elizabeth Street, Warkworth.

WALKING through the town, you wouldn’t know there was a potential public hazard from sewage overflow, apart from a couple of discreet signs that to read requires walking across a park sodden by flooding and overflow from the awa. Ongoing works and lines upon lines of orange cones mean that parking outside popular eating spots like the Bridgehouse Lodge is impossible. It’s not an inviting scene.

“We have 100 percent understanding where the businesses are coming from,” says Walters, “because we’re living it ourselves. Our livelihood’s gone down the drain. Trying to tell people of the sewage problem was hard because it wrecked our Mahurangi reputation but also Auckland Council and Watercare didn’t want the public to know. Not once in the five years did they put signs up saying there had been wastewater going into the river. It’s just so bad.

“Auckland Council didn’t tell the public about how high the risk was involved with sewage being right there. They cast the river – the Mahurangi River – as low-grade, non-recreational, and at very low public health risk. According to them, no one swims, fishes, kayaks, paddleboards, sails or anything in that river because that allows them to have discharge consent to be able to do what they’re doing. They write their own discharge consents. So they’re their own regulators.”

Watercare last week installed a temporary fix, something that Walters and other farmers and local businesses urged them to do at least five years ago.

“Auckland Council wouldn’t give us money for it. First, they just said no. Then last year, we begged them. At a meeting with Watercare, a lot of people were crying, asking can you please help us? Because we will not survive.

“Then Council and Watercare said yes, we can; they sat on the consents for nine months before anything happened. Watercare is now at least trying.”

Walters took a tour of the new treatment plant at Snells Beach.

“It’s beautiful. Just about finished. But they left the town’s pipes to the very last part. And the town of Warkworth has ancient old clay pipes, and it’s a mess of a system.”

While Jamie Sinclair maintains the interim fix will help, Walters is sceptical.

“The temporary fix won’t help if the overflow volumes are so huge. We found norovirus in our growing areas after only 60 cubic metres of an overflow. The last overflow was 180 cubic metres for 20mm of rain. Until they fix the stormwater, we will continue to be inundated. Regardless, the Mahurangi will still receive raw sewage into its arms due to a negligent council who would fine the bejesus out of anyone else for doing it.

“I’ve been told of places in Snells Beach that have sewage going through their backyard and into the river, very close to our oyster farms. I’ve had other people messaging about their properties having stormwater and wastewater coming through their place. The whole place is stuffed.”

There are ways to rebuild a broken infrastructure. But what this saga reveals is a systemic dysfunction.

Dr Mike Joy, fresh water ecologist at Te Herenga Waka (Victoria University), says a major problem is Auckland Council operating as its own regulator.

“I give the example of the Feilding Wastewater treatment plant that never complied with its resource consent conditions and their penalty for not complying is a sad-face stamp. It’s even worse when there’s not a separate council. I mean, that’s bad enough, but at least they can ring them up and say, ‘Look, you need to, you know, do something.’ And they can kind of threaten and jump up and down a bit.

“But when it’s all under the one organisation, then you’re not going to fine yourself. You’re not going to tell yourself off.

“So effectively, the police are running the drug den … the police are running the tinny house. So, who’s going to do anything? Nobody.”

While he can’t harvest, Walters is hands-on in trying to get the message out there and to find a resolution.

“I took [independent engineers] up to Kowhai Park, on Matakana Road, to look at manholes. One of them had tried his best to get the contractors to run CCTV up the lines, yet despite a whole week of fine weather, they failed to do so.

“When the heavy rain hit, the place resembled a lake of sewage. I watched full on grogans rolling down the grass into the drain. Ironically, the engineer who has also been very outspoken about the stormwater issue rang Watercare to lodge a complaint about it, Watercare sent their contractor, Downer out and within an hour they were trying to unblock the line up there. But it’s a serious blockage not just a fatberg or wet wipe issue. The Downer guys said to me that they would be back up the next fine day to send a camera up there which begs the question … how come they couldn’t do that in the beginning?”

While Auckland Council demands rural residents and farmers comply with strict regulations over septic tanks or run-off – key components of waterway degradation – there’s been around 2.2 million litres of sewage flowing into the awa river since April. Which begs the question, says Walters, “who’s the key component of degrading the waterways and the environment?

“[Council] were happy to profit from the growth and development at the cost of the environment and our livelihoods. It’s as simple as that. They allowed growth to occur before infrastructure, before that treatment plant was ready. And all we’ve got out of them was, ‘oh, the growth didn’t align properly’.”

As for the $55,000 counselling sessions Watercare has offered oyster farmers affected by a disaster not of their making:

“That’s quite an insult,” says Walters. “In the meantime, lots of us are hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, can’t pay our bills, can’t pay our mortgages, our kids aren’t getting fed, you know, things like that.”

Rubbing salt into the wound, oyster farmers in the region last year renewed leases on their farms with Auckland Council for 35 years.

“The lease isn’t fit for purpose when you’re spewing two million litres of sewage down the river because you couldn’t grow the place properly.”

Under the current system of governance, says Mike Joy, “you’re just not going to get good outcomes”.

“When it was Auckland Regional Council, they had a fantastic freshwater team who would have been up there, jumping up and down and kicking ass, but not now. That’s all under the one roof. And I’m sure that whoever’s running the outfit will be making sure that there’s never any problems for business or anything like that. And the little guys of course will be the ones that’ll be missing out and the environment will get trashed in the process. We see it happen everywhere.”

While Joy believes hypocrisy is rife in organisations such as Auckland Council, there are people within those organisations – like the freshwater team “who really do care and are trying to do the right thing. And I don’t know about Watercare … They’ve just been the dodgiest buggers I’ve ever had to deal with in my engagements with them over the Manukau harbour and wastewater treatment there.”

Last month, legislation making changes for councils passed its first reading removing the ‘four wellbeings’ – social, economic, environmental and cultural – from councils’ purpose and imposes a series of mandatory requirements.

Councils will need to prioritise core services.

The Minister for Climate Change, Simon Watts, is saying to hell with climate change, says Joy.

“There’s plenty of evidence of how [councils] have failed, that’s only going to get worse because Simon Watts is telling them to back off and just take out the trash.”

Ngāti Manuhiri is the kaitiaki of Mahurangi and surrounding waterways. Not just in a physical sense, through monitoring and restoration – the care goes deeper, says spokesperson Delma O’Kane-Farrell.

“The river is part of who we are. Ko Awa Mahurangi au, ko au Awa Mahurangi – I am the river, and the river is me. Our role is to protect its mauri, to make sure it continues to sustain life, and to pass that responsibility on to those who come after us.”

Many of the overflows and discharges may be considered ‘legal’, says O’Kane-Farrell, but that doesn’t make them acceptable when you look at their impact on the awa. “The system needs to shift to acknowledge that.”

The overflow has had enormous consequences, says O’Kane-Farrell.

“The repeated overflows have had a huge impact from our perspective as kaitiaki. It’s not just about water quality — it’s about the mauri of the awa being compromised. Our relationship with Mahurangi is whakapapa-based. When the river is unwell, our people feel it deeply.”

The iwi has met regularly with Watercare and Auckland Council, and have also hosted local oyster farmers to talk through the shared impacts on the harbour.

“We’re doing the mahi,” she says, “but the root of the problem lies in the failure of central and local government to plan ahead. Development has continued at pace in the wider area, yet the infrastructure hasn’t kept up. The system is under immense pressure — and while growth continues, the awa, the moana, and our communities are bearing the cost.”

Works outside the Bridgehouse Lodge in Warkworth

Ngāti Manuhiri Settlement Trust

MEANWHILE, Watercare and Auckland Council have been blaming each other. Jamie Sinclair, however, maintains Watercare has an effective relationship with Auckland Council:

“I think we have a good relationship with the council actually. We are a strategic partner for them as well as being a subsidiary of Auckland Council. We work alongside them in executing on the future development strategy which is where the plans and the plan is for Auckland to grow … But it’s not a perfect science either.

“We know that growth happens sometimes when we don’t expect it and happens faster or slower or in different areas or we see private plan changes as well. So that’s where a developer would like to develop in a particular area. They can request a private plan change and that will open up an area for development that perhaps hadn’t been part of the original plan.

“So that changes the way that we need to again prior focus our attention to make sure that we are not leaving Aucklanders without necessary wastewater infrastructure, but we can’t turn these things around tomorrow. That’s large and complex and requires a lot of design and a lot of pieces of the puzzle to be in place before the infrastructure can be enabled.”

There are nine oyster farmers in the region. A mixture of retail and wholesalers.

Employment in the town is also affected, because you can’t hire labour when there’s no oysters to shuck or process. Bigger corporates like True South Seafood wanted Mahurangi oysters to export.

Says Walters: “They should be rocking and rolling and employing local people, at least upwards of 30 or more, and they can’t do anything. It’s not just the implications for the sewerage in terms of our waterways and our food sources and our producers and businesses, but it’s employment, right? There’s many elements to it, and they’re all just as important as each other.

“It’s heartbreaking. The people in power have the ability to say ‘we can help you out a little bit’. We’re not looking for millions of dollars or redress – we just need to be able to survive to make it because the problem won’t be fixed permanently until 2027.

When that happens, there’ll be upwards of 30,000 people turning up to Warkworth and Matakana. Currently the figures are estimated at 7,000. In the next 10 to 15 years, says Walters, all the surrounding hills are going to get sculptured and carved. All the roads will lead to the sea.

“Regardless of whether the sewage issue is fixed, there’ll be further environmental degradation,” says Walters.”

LIFE for Walters is governed by the tide. On the day of our interview, he should’ve been out checking the farm, which is a 15 minute barge ride from Scott’s Landing.

Walters is also thinking of the legacy and his children, who’ve grown as the business has grown.

“I’ve got three kids. Two of them are older, 18 and 21 this year, and I’ve got a 15-year-old. It’s been their lives. With me being here over weekends, I’m running off a skeleton crew now. I’m struggling to pay my one and only employee. Plus Julie, who’s in the shop.

“You can’t do this job without help because you can’t physically grow oysters. Half of my day is spent on a tide, a low tide, working my farm, which I haven’t been able to do for a few months now just because of everything that’s been going on. But I almost can’t even afford to go out there because, you know, the fuel and the gear and equipment – it all costs money, money that we don’t have.”

It’s a sustainable operation. “We catch our own oysters on wooden sticks in summertime; you give them like an algal garden and a sea view and hope that they settle. And then it’s a cycle: you harvest the mature sticks, you put out the baby sticks. If you can’t harvest your mature oysters because you’ve got no home for them, because they’re polluted, the cycle breaks down.

“So right now, there are full farms that can’t be harvested.”

Reputational damage takes far longer to fix than a polluted waterway.

“That’s massive. You’ve got to educate people, but there will be a lot of people that just won’t trust regardless and completely understand that. I mean, the testing regime is quite world-class, but it will take time for us to be able to build that reputation back up with a Mahurangi oyster.”

The worst case scenario, says Walters, is he’ll be liquidated.

“My farms are only worth probably a dollar now because who’s going to buy an oyster farm in the Mahurangi Harbour? It cost me a hell of a lot of money to re-lease the farm. What would I do? I’d have to walk away and do something else but this is the life I’ve known since I was 18. I’m now 45, so that would be difficult.”

Recently the community rallied to do a fundraiser for Walters.

He points to a pair of bright blue gumboots with handwritten messages from those who turned out to support him.

“They all wrote lovely slogans on them. You know, it’s just I guess I have poured my heart into and it is broken; it’s breaking pretty badly now.

“It does get you a little bit emotional at times. There’s a lot of love and support and community support out there. I didn’t know how loved the place was. It’s what carries me right now.

“It’s hard to catch up and still survive because. What was 100 mils of rain a couple of years ago is now 10 mils of rain to get us to the same amount of overflow.”

Jamie Sinclair concedes the radical shift in climate related events challenges existing infrastructure.

“There’s no doubt that storms and significant weather events do create challenges for the network as a whole. There is storm water and storm water does have inundation infiltration if you like into our network at times that creates challenges because it does increase the load that goes through our systems and that’s where you’re seeing some of the overflow issues.

“I’m actually very proud of the work that Watercare does in terms of water and wastewater provision for Auckland and I accept that there are some challenges and Walkworth is a challenge. Absolutely. And I’m not going to discount the effect that overflows are having on the business community or the oyster farmers in particular. I think that is going to be a very hard position for them. So look again I think we are trying to solve this problem as quickly as we can.”

Ngāti Manuhiri wants to see genuine partnerships where iwi are involved from the start — not just consulted after decisions have already been made. “That means proper planning that reflects the true limits of the environment, not just what can be signed off through consent conditions,” says Delma O’Kane-Farrell.

“We also want to see meaningful investment in restoration and practical steps that prioritise the long-term health of the river. It’s not enough to respond after damage is done — we need to work together to prevent harm in the first place, and to ensure this doesn’t happen again — here, or in any of our other waterways.”

Dr Mike Joy believes the woes in Warkworth and Mahurangi are symbolic of a Faustian bargain in growth and development.

“If you just look a bit deeper, then GDP is the best measure we have of environmental destruction. Of all of the indexes we’ve got for measuring environmental destruction, if you test them all, GDP comes out as the best predictor of harm. So we have this dilemma here – greenhouse gas emissions are locked completely into GDP growth.

“The thing that we try to maximise and everyone goes on about, a healthy economy, blah, blah, blah. If only people could understand that what that means is that your goal in life is trashing the environment. Only it’s not phrased like that. It’s phrased as, you know, a healthy economy. But what it really is is burning fossil fuels and digging up non-renewable resources and screwing the place.”

Walters is staunchly walking the line.

“You can’t have it both ways. You can’t have the growth and the, wow, look at us, we’re growing, and then the, whoops, we forgot to take care of business.

“I might be walking away with nothing. But, you know, it’s not just about the money aspect. I do this to make people happy. And it can bring such happiness to their eyes and hearts, and that’s a rare thing to be able to do, to be able to touch people in that way.”